Name That Tune

This week’s Name That Tune was submitted by Listener Jeremy. Here’s your (big) hint: this is from a concert(in)o!

As always, your goal is to provide as much accurate analysis as possible. First try to get the nationality, year, and genre, then make educated guesses about the composer and — if possible— the piece. If you know the piece immediately, send us an email at toneprose@substack.com instead of commenting so the rest of us can have fun guessing.

Last Week’s Results

Tone Prose 159

Mozart, Adagio in B minor

Joseph identified the piece exactly and immediately. Apparently, his high school piano teacher (whose name — I kid you not — was/is Dick Van Dyke) was a big fan.

However, Beethoven turned out to be the most popular guess, with Listener Kevin making a rare miss, and Listeners Gregor and Laurie also joining the bandwagon. Listener Eric also guessed Beethoven but was sly enough to hedge his bets by adding Mozart to the barrel, so we’ll give him a win too.

Think you can stump your fellow Listeners? Go ahead and try!

Head to our Google Form to submit a YouTube link OR upload your own 30-second clip of an unidentified piece of classical music for us to try to identify.

Comp Lesson

A few weeks ago when I did the call for AMA questions for the Tone Prose 3rd Anniversary, I specified that I was interested in answering some questions about the teaching of composition, because it’s an endeavor that I’ve been exploring more lately, and naturally I’m starting to theorize about it.

I got a few questions but I decided to save this topic for a week when there weren’t any news stories that caught my attention, so I’m going to use this edition as a first chapter in a series.

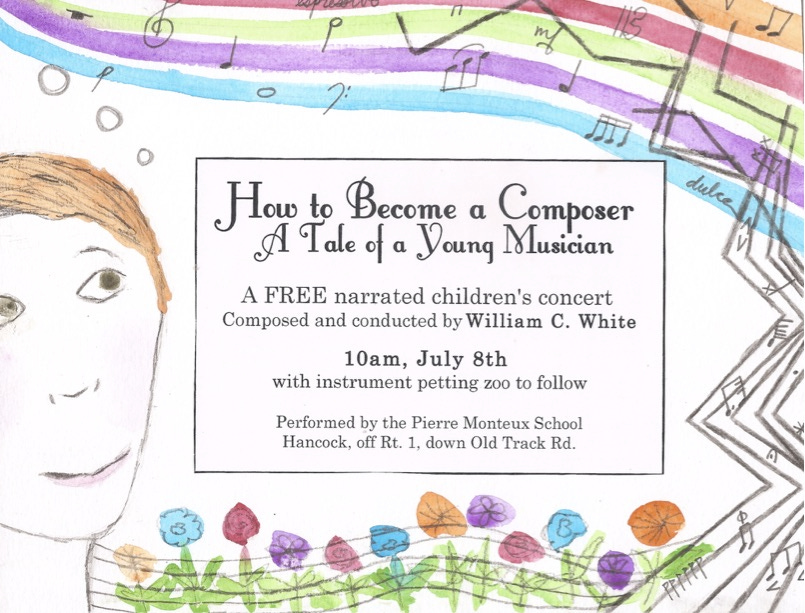

I’ll start off by saying that I addressed the larger question of how (or, more properly speaking, why) to become a composer in one of my long-lost pieces for young audiences about a decade ago (which you can listen to if you’re so inclined.) But I digress

Ludwig van Beethoven and My College Roommate

Let’s start with Beethoven, because he famously said almost nothing about how he composed aside from two cryptic statements:

When asked why, during the process of composition, he had reworked a passage or changed a detail, his standard response was, “because it’s better that way.” Words to live by.

When anyone really tried to nail him down about his compositional process, his honest answer was that improvements to a composition could be made by making the details relate to the whole (and vice versa.)

Next, a little story: the year after I graduated college, I moved into a grungy Hyde Park apartment with two friends. One night, we were talking about a composition that I was working on, and I mentioned something to the effect that I was exploring a particular area of music theory in the piece. This prompted a rather surprised reaction from one of my roommates. “Theory? What?” and I said, “yeah, music theory” and he goes, “Theory? Really? I thought you just kinda try to make something that sounds good.”

My other roommate — a music lover with a jazz piano background (also a Tone Prose reader) — jumped in and defended the notion that music theory is a thing that exists, and that it informs composers and musicians.

Of course, at the time, roommate #2 and I thought that roommate #1 had proven himself a right dope. (In fairness, roommate #2 was getting a masters in philosophy, so his whole concept of “theory” was limited to the writings of Jacques Derrida and Pierre Bourdieu.)

Obviously, roommate #2 and I were correct then and remain so now. But in another way, roommate #1 said something really perceptive: a huge part of writing music is just trying to come up with something that sounds good!

Material and Tools

The point of that story is that when you’re writing music, you have to do two things:

Generate material, i.e. the stuff that (hopefully) sounds good

Manipulate the material using compositional tools in order to create long forms that generate and retain a listener’s interest for a given span of time.

Now look, there’s a lot of people who write music who don’t care about that second item: songwriters, tunesmiths, pop producers — basically anyone whose goal is to retain your attention for no longer than a minute or three. But if you want to be a composer in the classical tradition, you’ve got to acquire the tools to do stuff with your material.

It’s similar to having a pretty voice versus a bunch of vocal training. You can learn everything about breath support, larynx position, vowel formation, languages, and repertoire, but those can only get you so far if you don’t have a naturally appealing vocal timbre.

And just as the intrinsic beauty of a lovely voice can be teased out as part of a singer’s training, so can a composer’s instincts for developing quality material be strengthened. But the crucial word is “instincts” — if the instincts aren’t there, all the tools in the world won’t get you very far.

A Few Tips

I’ve got plenty more theory to drone on about in future editions, but I’ll end with a couple tips (which I’ll flesh out later on):

Don’t get bogged down in a “concept” for your piece. Music is like a vine; you can prune it, but you’ve got to let it grow organically, and the concept that gets you started might not be what gets you to the finish line.

Every piece should have something in it that embarrasses its composer.

mf and mp are loser dynamics for weaklings. Take a stand!

If you’re struggling with a passage, throw it out and try something simpler.

Tone Praise

William Bolcom, Seattle Slew Orchestral Suite

I’m conducting a program this week that includes William Bolcom’s violin concerto, a bona fide American masterpiece, if you ask me, and it reminds me of my first encounter with this composer’s music, which is when I played Seattle Slew in college at the University of Chicago. I still give our orchestra’s conductor, Barbara Schubert, a lot of credit for choosing unusual repertoire, and I recall having had an absolute blast playing this piece.

I know precious little by Bolcom aside from these pieces (and a handful of his Rags) but that needs to change — he’s clearly a major voice and among best of the late 20th-century American composers in terms of connecting craftsmanship to musicality.

Tone Prose is a co-production of William White, Joseph Vaz, and the Listeners (i.e. you.)

I enjoyed the top tips, especially in relation to Ludwig VB - I wonder if we could get a recurring series about "Compositional Tips from X Composer." Though I guess that's not really TP's main MO.

And I'll also recommend some Bolcom, his "Twelve New Etudes" which are at this point 'new music canon' for pianists: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PL9uF9x6KXIDQF8l9t7mWqg9RMMB42GXV7&feature=shared

I wholeheartedly endorse getting to know more Bolcom. As with everything, Tone Prosaics should turn ear to the clarinet: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=OLAK5uy_kLZG0md3FySxhiq6ek69v0DY4zNQIRloU&si=VmuyKMzo91RupjAY