Name That Tune

This week’s Name That Tune is a Maestro Will special. Here’s your hint: this piece is scored for an instrumental choir. A trombone choir, for example, is an ensemble of trombones (say, between 4-8). If you can figure out the instrument that these musicians are all playing, it will be a dead giveaway to the identity of the composer, since this instrument is associated with him and him alone!

As always, your goal is to provide as much accurate analysis as possible. First try to get the nationality, year, and genre, then make educated guesses about the composer and — if possible— the piece. If you know the piece immediately, send us an email at toneprose@substack.com instead of commenting so the rest of us can have fun guessing.

Last Week’s Results

Tone Prose 79

Fauré, 13 Nocturnes, op. 74: No. 7

Another week, another honest-to-god winner: Listener Eric wrote in with the exact work! Listener Jeremy included Fauré in his basket, an impressive feat in and of itself.

For my part, I (Will) got sort of close with Saint-Saëns, and if I hadn’t been totally exhausted and ready to give up, I probably would also have also wrongly guessed Charles Thomlinsen Griffes. Listener Laurie took the American route and guessed Gershwin, in what will surely go down as the most epic NTT-related comment in Tone Prose history, the main gist of which was that you all need to attend (in person or virtually) Harmonia’s April 6th concert, about which, more below.

Think you can stump your fellow Listeners? Go ahead and try!

Head to our Google Form to upload a 30-second clip of an unidentified piece of classical music for us to try to identify.

Rant

First, the good news: on Saturday, April 6, a truly momentous occasion will take place in Seattle, surely an event of major interest to Tone Prose readers worldwide, when Young Joseph “Joey” Vaz performs as soloist with the Harmonia Orchestra in George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue (see above.)

The rest of this post is devoted to why the publisher of Rhapsody in Blue, European-American Music, has abused its copyright privileges to offer a substandard product to interpreters of this work, and thus made the correct execution and performance of Gershwin’s music much more challenging than it should be. And while I (Will) am happy to name and shame EAM, they are simply representative of the industry-wide malfeasance. The real problem though, is the law itself.

What is Copyright?

Essentially, a copyright is a monopoly on a piece of intellectual property, such as a book, movie, recording, or, in the present case, a piece of music.

Now I don’t think you have to be the most rapacious libertarian capitalist in the world to reach the conclusion that monopolies are bad. But you don’t have to be a pinko commie tool to think that a limited monopoly granted to an artist might be good. After all, if you create an original work, shouldn’t you get some period of exclusivity in which to exploit your creation?

The first copyright law in the United States, the Copyright Act of 1790, did just that: it gave authors exclusivity on their works for a period of 14 years with an optional 14 year extension. That, I will grant, is a reasonable way of doing things. Of course, if you create a successful bit of IP, you’ll want to exploit it for as long as possible, so as corporations came on the scene and lobbyists started doing their dirty work, the original copyright provisions got distended to grossly disproportionate forms, culminating in the famous “Sonny Bono” Act of 1998. Cui bono? Sonny!

[A brief aside: don’t let Sonny Bono’s cameo on The Golden Girls fool you — he was one bad hombre. Aside from his rotten-to-the-core copyright extension act designed to protect Disney’s copyright on Mickey Mouse, he was also a raging NIMBY exclusionist zoning champion as mayor of Palm Springs, and gave Newt Gingrich PR advice.]

The Baroque State of U.S. Copyright Law

In the US, we are currently operating under a dual copyright regime:

For works created prior to 1978, the maximum copyright duration is 95 years from the date of publication, or 120 years from the date of creation, whichever is shorter.

For works created in or after 1978, the maximum copyright duration is “life of the author” + 70 years.

As to the question of Rhapsody in Blue, attentive readers of Listener Laurie’s comment will have noted that 2024 is the centennial of this great masterpiece of symphonic jazz. So, you might ask yourself, shouldn't the music be in the public domain? Can’t you just download the parts from the Internet Music Score Library Project? Why does a publisher have to be involved at all?

Enter Ferde Grofé

First thing first: the original score of Rhapsody in Blue *is* in the public domain, and you *can* download it from imslp. The problem is, the original version of Rhapsody in Blue isn’t the version that anyone actually plays.

Well, it’s not *no one* who plays it — in fact, there’s a very cool recording of the original version, scored for Paul Whiteman’s dance band in 1924, performed by George Gershwin himself on a piano roll, with MTT conducting. (The tempi are nuts.) But Gershwin didn’t *orchestrate* the Rhapsody. That job was left to American composer Ferde Grofé (of “On the Trail” fame). Grofé revised and expanded this version in 1926, but it wasn’t until 1942 that he scored it for a normally-constituted symphony orchestra, and that’s now the version that “everyone” plays.

Material Interests

This 1942 version of Rhapsody in Blue remains under copyright until 2038. Which means that the publisher, European-American Music, retains a monopoly on the performing materials for another 14 years.

As we all know, the problem with a monopoly is that the monopolizer has no incentive to provide their customer with a decent product or service, and that’s exactly the problem here. First off, I placed Harmonia’s rental order for these materials back in May of 2023. I signed a contract that stated exactly when the sheet music was to arrive. That date came and went, and when I contacted EAM, it turned out they had lost track of the order.

Then things got worse: EAM sent me a freshly printed set of parts. These parts were engraved in 1942 using 1942 technology and 1942 Broadway notational conventions. When you first glance at the music on the page, it doesn’t look too shabby. But take a closer look:

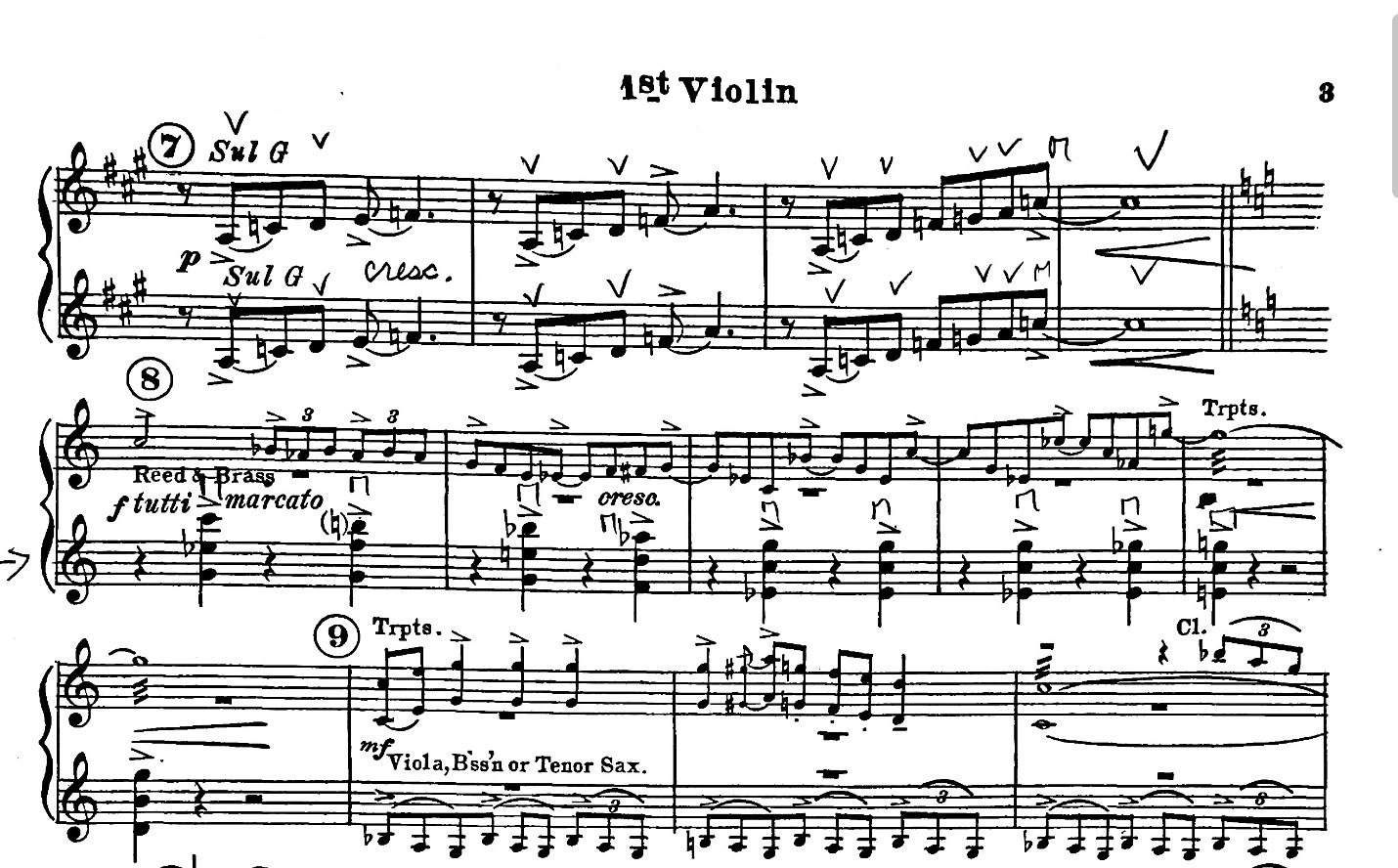

Notice, for example, that after the first line of music, the clef is never re-printed, and neither is the key signature. That’s very poor indeed. The problems don’t stop there though: these parts were written so that the piece could be performed with any hackneyed, ill-constituted civic band, and so the parts are laden with cues to such an extent that they are almost impossible to read. This tendency reaches its ne plus ultra in the first violin part, which is clearly designed as a quasi conductor’s score for concertmasters who are also the leaders of their bands.

Errata

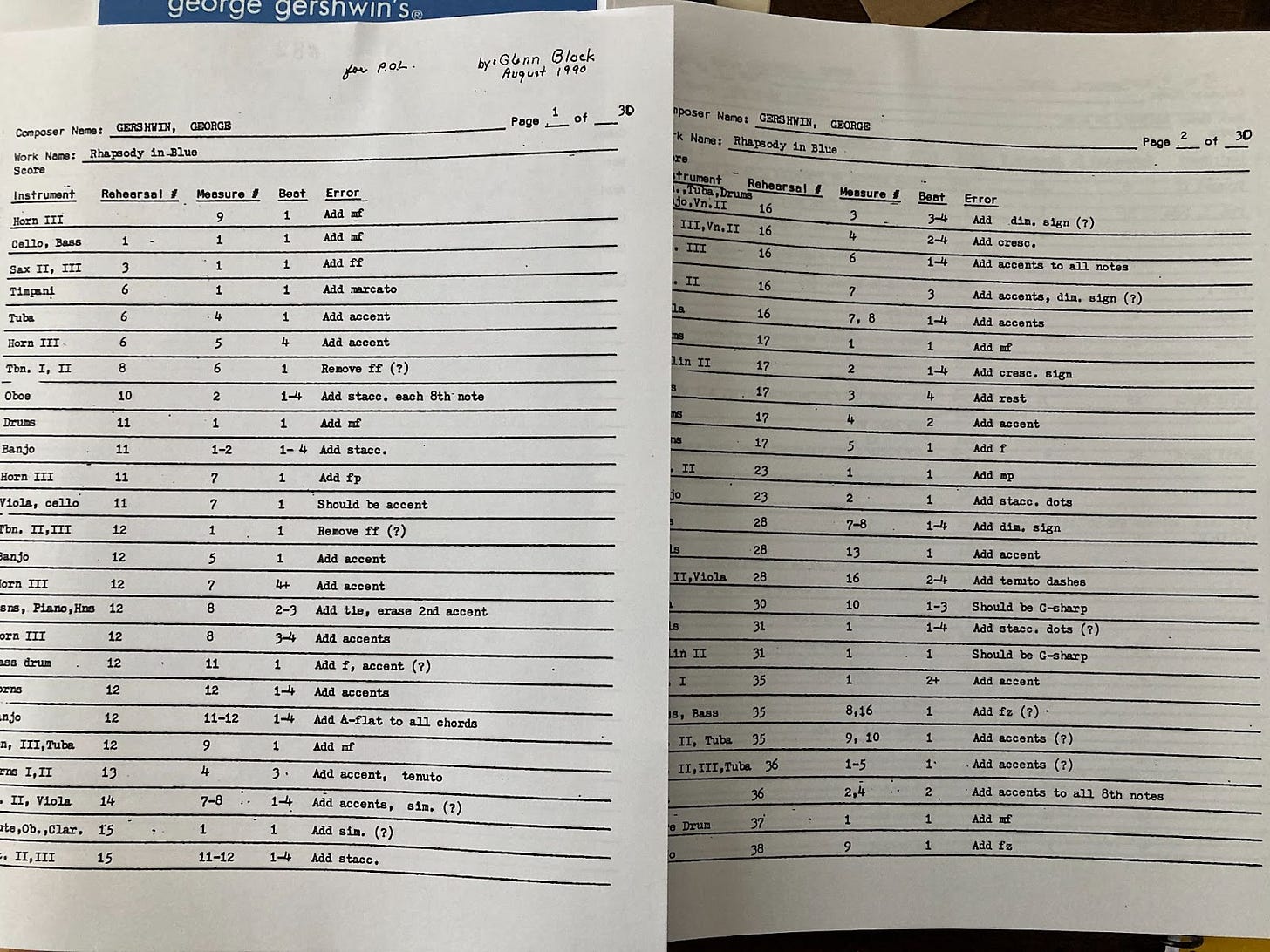

And now for the pièce de résistance: EAM doesn’t just sent the parts, they also send a printout of the 30-page errata list of corrections that need to be marked into all the parts.

Just think about this for a second: the parts were engraved in 1942. This errata list was compiled in 1990. That means that the publisher has had 34 years during which they could have re-engraved the piece so as to incorporate all these corrections.

But why would they? That might cost... oh a few thousand bucks I guess? It’s so much easier to make the renters of this material do the work themselves (as I did.) Who are the renters going to complain to? What competitor are they going to turn to? There is none — that’s the whole point of a monopoly!

Bad Actors, Bad Incentives

This whole thing reminds me of the problem with drivers.

Bad drivers should certainly be held to account for speeding and running stop signs. It’s antisocial behavior that can easily get people hurt or killed. But the real criminals are the transportation engineers and urban planners who have designed the road infrastructure that encourages speeding. The real criminals are the lobbyists who have been working on behalf of the auto manufacturers for a century to ensure that America is designed for car dependence. The real criminals are the lawmakers and politicians who have created a permissive legal structure where killing someone with a private automobile isn’t even considered a case of criminal conduct.

As long as the law stays the same, there’s nothing I can do about this shameful state of affairs, but thank god I have a newsletter, ya know?

Tone Praise

Telemann, Grillen-Symphonie

Telemann’s “Cricket Symphony” is scored for piccolo, alto chalumeau, oboe, violins, viola, and two double basses. Calms the nerves after a day spent contemplating copyright lice!

Tone Prose is a co-production of William White, Joseph Vaz, and the Listeners (i.e. you.)

Tone Praise: Oh chalumeau! be joyous, for just as the cricket will moult from larva to adult, so too shall you develop into the clarinet.

NTT: Sounds like a theremin to me... but who is associated with theremin? Mr. Theremin??